Organizations invest significant resources training proprietary machine learning (ML) models that provide competitive advantages, whether for medical imaging, fraud detection, or recommendation systems. These models represent months of R&D, specialized datasets, and hard-won domain expertise.

But what if an attacker could duplicate an expensive machine learning model at a fraction of the cost?

Model extraction is an emerging threat to any organization exposing ML capabilities through APIs. Using only standard API access, the same access any legitimate user would have, an attacker can build a substitute model that mirrors the target’s behavior with alarming fidelity. No access to training data. No knowledge of the model architecture. Just queries and responses.

This attack is a form of model theft called model extraction, and it’s a growing threat to any organization exposing proprietary machine learning models through APIs.

What Is Model Extraction?

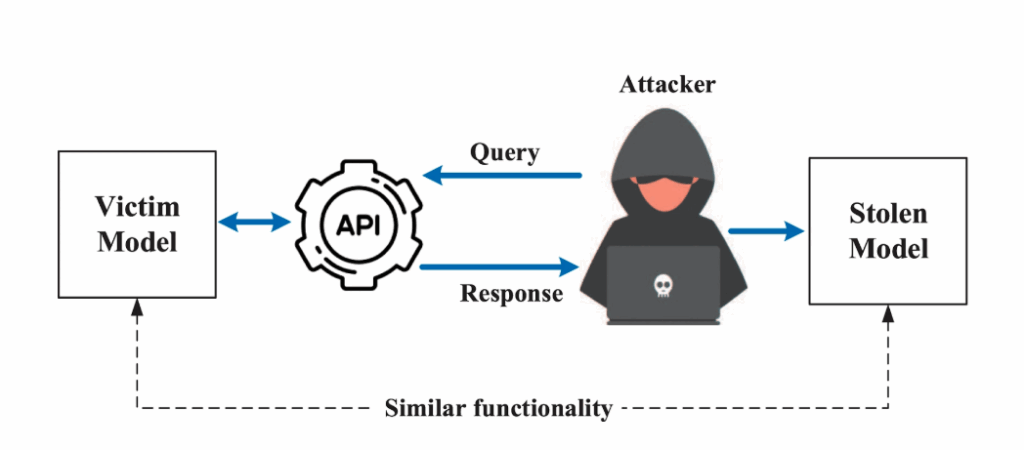

In a model extraction attack, an adversary with query access to a ML model can steal the model’s underlying functionality by systematically querying it and using the outputs to build a replica model that mimics the target’s behavior. The attack follows a straightforward pattern:

- The attacker sends carefully crafted inputs to the target model’s API

- The attacker records the model’s responses to build a dataset of input-output pairs

- The attacker trains their own “stolen” model using this collected data

The key insight in this attack relies on the fact that soft probability outputs contain far more information than hard labels. For example, when a model that classifies shoes returns “80% sneaker, 15% ankle boot, 5% sandal,” it reveals learned relationships between classes, which are relationships the attacker can abuse to train a highly effective replica.

The Attack Scenario

The ML model in this attack scenario is a convolutional neural network (CNN) designed for image analysis. CNNs are compact AI models optimized for computer vision tasks, an earlier generation of technology compared to today’s large language models, but still powering critical applications from facial recognition to diagnostic imaging systems.

The applications that use these CNNs analyze images and return identified regions of interest. From the outside, we have no visibility into the model’s architecture, training data, or internal weights. We can only submit images and observe outputs, in a classic zero-knowledge fashion.

Building the Training Dataset

Our attack dataset consisted of 100 images extracted from publicly available sources. Each image was uploaded to the target system. After the model’s analysis was completed, it returned its predictions, effectively providing us with “expert labels” for free.

We saved each input alongside its corresponding output, creating pairs of input and output. We repeated the process 100 times, resulting in a training dataset built entirely from API responses.

Training the Stolen Model

We then trained our own CNN using these collected pairs. To improve performance, we implemented measures to address the class imbalance inherent in the target domain, where regions of interest typically occupy a small portion of each image.

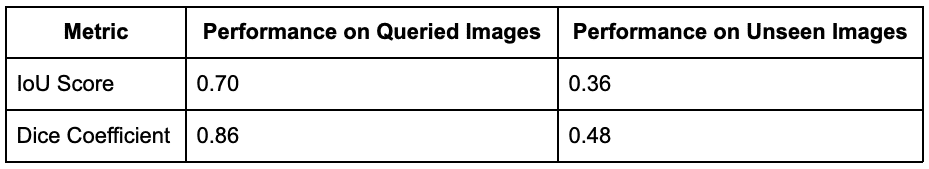

To assess our model, we used two metrics – Intersection over Union (IoU) and Dice coefficient. IoU measures how accurately the AI’s prediction matches the actual result. Consider two overlapping regions: one representing the AI’s detection and one showing the ground truth. IoU calculates the overlapping area divided by the total combined area – a score of 1.0 indicates perfect alignment, while 0 indicates no overlap. The Dice coefficient evaluates how well predictions match reality by calculating 2 × (overlap area) ÷ (total area of both regions). It ranges from 0 (no match) to 1.0 (perfect match), giving more weight to the overlapping region than IoU does.

After training for 50 epochs, our stolen model achieved:

Although these scores aren’t cutting-edge, they demonstrate a worrying degree of success given the limited resources employed. The replica model had learned to identify the same patterns as the proprietary system using only 100 queries.

Through additional training rounds, a higher volume of queries, and improved architecture, an adversary could achieve considerably stronger performance, potentially nearing that of the original proprietary model.

Demonstrating the Attack: A Reproducible Example

To illustrate the attack, we built a fully reproducible demonstration using Fashion-MNIST, a dataset of clothing images that serves as a stand-in for any image classification API.

The Setup

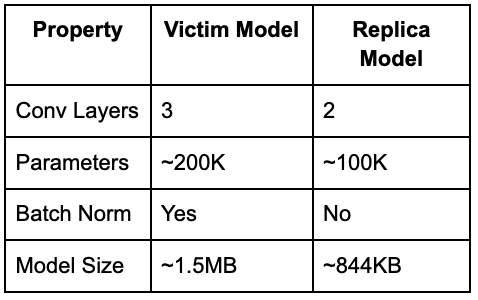

Target Model: A CNN with 3 convolutional layers and batch normalization

- ~1.5MB model file

- 91% validation accuracy

- Represents a proprietary model behind an API

Attacker’s Constraints:

- No access to training data

- No knowledge of model architecture

Can only query the API and observe softmax probabilities

Phase 1: Query Collection

The attacker sends images to the victim’s API and records the soft probability outputs:

Python

with torch.no_grad():for images, _ in query_loader: # Ignore true labels - attacker doesn't have them!images = images.to(device)probs = victim_model.predict_proba(images)query_images.append(images.cpu())soft_labels.append(probs.cpu())

Notice that we discard the true labels entirely. The attacker doesn’t have access to ground truth, only the victim model’s confidence scores. But those confidence scores are enough.

Phase 2: Knowledge Distillation

The core of the attack is knowledge distillation training a student (replica) model to match the teacher’s (victim’s) probability distributions rather than hard labels:

Python

def knowledge_distillation_loss(student_logits, teacher_probs, temperature=3.0):"""Soft target loss for knowledge distillation.

Higher temperature produces softer probability distributions."""soft_student = F.log_softmax(student_logits / temperature, dim=1)loss = F.kl_div(soft_student, teacher_probs, reduction='batchmean')return loss * (temperature ** 2)

The temperature parameter controls how much the probability distribution is “softened.” Higher temperatures reveal more information about the relationships between classes, making it easier for the stolen model to learn the victim’s decision boundaries.

Phase 3: The Replica Model

Our replica model uses a deliberately different, simpler architecture to demonstrate that model extraction works even when the attacker doesn’t know the victim’s architecture. The stolen model learns to mimic behavior, not replicate structure. The following table compares the architecture of the victim model and the replica model.

Results: The Attack Works

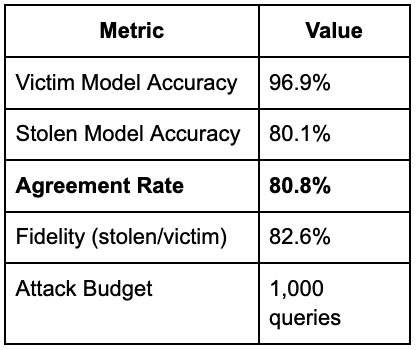

After just 1,000 queries and 20 training epochs, the replica model achieved an accuracy rate of 80.1%. The following table shows the replica model’s performance.

The agreement rate is how often the stolen model’s prediction matches the victim’s, the key metric. At 80.8%, the stolen model reproduces the victim’s behavior on 4 out of 5 inputs.

Visual Evidence

Let’s analyze the replica model’s performance from a visual perspective using predictions, confusion matrices, and per-category agreement rates.

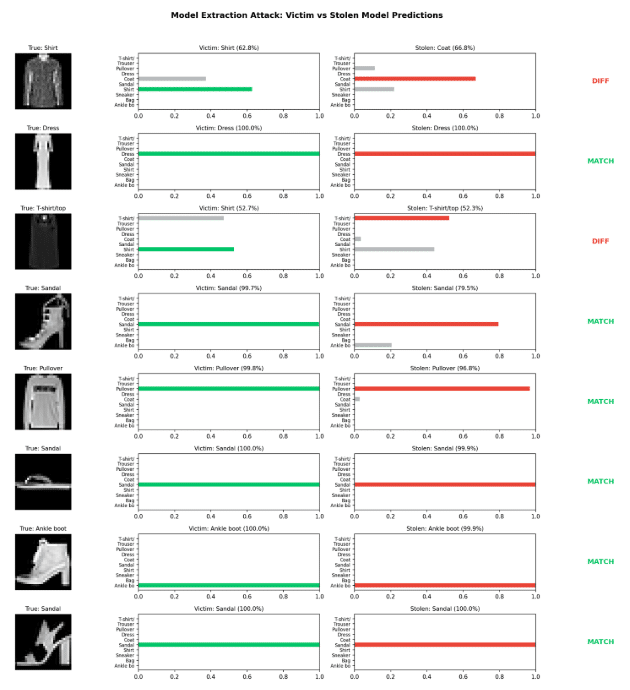

The comparison grid below shows side-by-side predictions on sample images. Green indicates agreement; red indicates disagreement:

Notice how even when both models are wrong, they’re often wrong in the same way. The stolen model has learned the victim’s decision boundaries, including its failure modes.

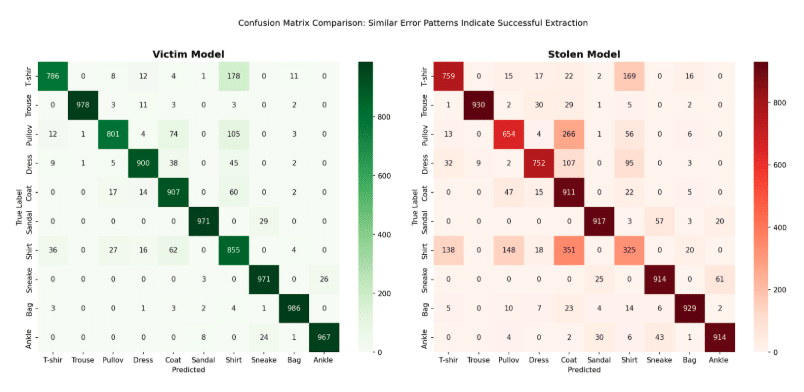

The confusion matrices reveal similar error patterns between models, a hallmark of successful extraction:

Both models struggle with the same categories (Shirt vs. T-shirt/top, Pullover vs. Coat). The stolen model inherited the victim’s biases.

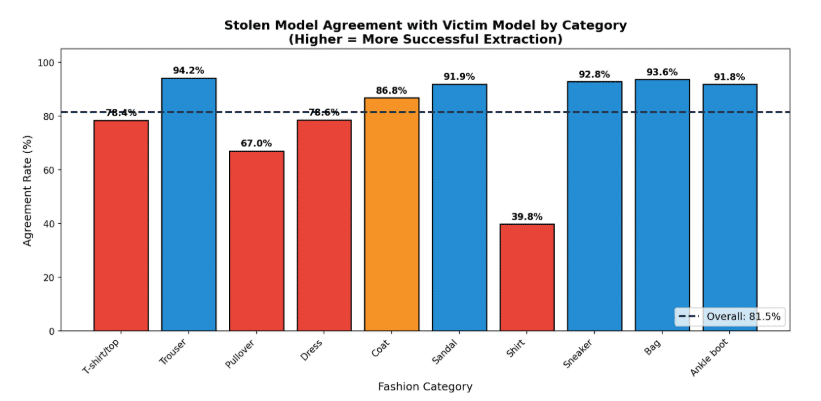

Per-category agreement rates show extraction success varies by class complexity:

Simple, distinctive categories (Trouser, Bag, Sneaker) show >90% agreement. Ambiguous categories (Shirt, Pullover) show lower agreement, but still track the victim’s confusion patterns.

Why This Matters

Model extraction enables several downstream attacks:

IP Theft: Months of R&D, proprietary training data, and domain expertise can be stolen through API access. The attacker gets a functional copy without the development costs.

Adversarial Attack Development: Stolen models enable white-box attack development against black-box APIs. Once you have a local copy, you can craft adversarial examples at leisure, then deploy them against the production system.

Cost Arbitrage: Attackers can resell cheaper inference using the stolen model, undercutting the original provider while free-riding on their R&D investment.

Competitive Intelligence: Even imperfect extraction reveals what features a competitor’s model has learned to prioritize, informing product strategy.

The Architectural Flaw

Many organizations assume that keeping model weights private is sufficient protection. The logic seems sound: if attackers can’t download the model file, they can’t steal it. But this creates a false sense of security. In reality, behavior is the model. Every query-response pair is a training example for a replica. The model’s behavior is exposed through every API response. Soft probability outputs are particularly information-rich; they reveal not only what the model predicts but also how confident it is and what alternatives it considered.

Mitigations

Effective defenses require treating model outputs as sensitive information:

Rate Limiting: Restrict query volume per user to prevent the bulk data collection needed for training replica models. Our attack used 1,000 queries, a number that should trigger anomaly detection.

Output Perturbation: Add calibrated noise to confidence scores. This degrades the information available for distillation while maintaining utility for legitimate users.

Prediction Truncation: Return only top-k classes or hard labels instead of full probability distributions. Less information per query means more queries required for extraction.

Behavioral Monitoring: Flag suspicious patterns like rapid uploads of diverse images, sequential queries with slight variations, or systematic coverage of the input space.

Watermarking: Embed detectable patterns in model behavior that survive extraction. If a stolen model appears in the wild, watermarks provide evidence of theft.

Query Pattern Analysis: Legitimate users have characteristic query patterns. Extraction attacks look different, more systematic, more diverse, more evenly distributed across the input space.

Conclusion

Model extraction attacks transform API access into model theft. The attack requires no special access, just the same query capability available to any legitimate user.

Our demonstration achieved 80% behavioral replication with just 1,000 queries. A determined attacker with more patience and compute could approach near-perfect extraction. The proprietary model you spent months developing could be replicated in hours.

The core lesson: Your model’s behavior is your model. Every API response teaches attackers something about your system. Protecting the weights while exposing unlimited queries doesn’t eliminate the risk of theft, it simply shifts the attack surface from file exfiltration to behavioral replication.

The organizations that take model extraction seriously should implement defense-in-depth: rate limiting, output perturbation, behavioral monitoring, and incident response plans for detected extraction attempts.

The organizations that don’t will discover their proprietary models aren’t as private as they thought.

Praetorian helps organizations assess and secure their AI systems against emerging threats like model extraction. To learn how we can evaluate your ML infrastructure’s security posture, visit praetorian.com or contact our team.